- Home

- Tim Crouch

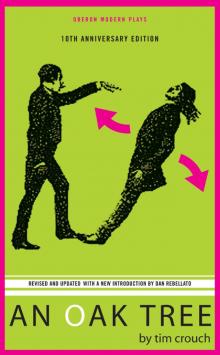

An Oak Tree

An Oak Tree Read online

AN OAK TREE

Tim Crouch

AN OAK TREE

10TH ANNIVERSARY EDITION

UPDATED AND REVISED

WITH A NEW INTRODUCTION BY DAN REBELLATO

OBERON BOOKS

LONDON

WWW.OBERONBOOKS.COM

First published in 2005 by Oberon Books Ltd

521 Caledonian Road, London N7 9RH

Tel: +44 (0) 20 7607 3637 / Fax: +44 (0) 20 7607 3629

e-mail: [email protected]

www.oberonbooks.com

Copyright © Tim Crouch, 2015

Introduction copyright © Dan Rebellato, 2015

Reprinted in 2006, 2011

Reprinted with revisions and updates in 2015

Tim Crouch name is hereby identified as author of this play in accordance with section 77 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. The author has asserted his moral rights.

All rights whatsoever in this play are strictly reserved and application for performance etc. should be made before commencement of rehearsal to United Agents, 12-26 Lexington Street, London W1F 0LE ([email protected]). No performance may be given unless a licence has been obtained, and no alterations may be made in the title or the text of the play without the author’s prior written consent.

You may not copy, store, distribute, transmit, reproduce or otherwise make available this publication (or any part of it) in any form, or binding or by any means (print, electronic, digital, optical, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

PB ISBN: 978-1-84002-603-0

EPUB ISBN: 978-1-84943-583-3

Cover design by Julia Crouch

Printed, bound and converted

by CPI Group (UK) Ltd, Croydon, CR0 4YY.

Visit www.oberonbooks.com to read more about all our books and to buy them. You will also find features, author interviews and news of any author events, and you can sign up for e-newsletters so that you’re always first to hear about our new releases.

Contents

Prologue

Scene 1

Scene 2

Scene 3

Scene 4

Scene 5

Scene 6

Scene 7

Scene 8

By the Same Author

INTRODUCTION

This book is a gallery.

Tim Crouch once described words as ‘the ultimate conceptual art form’. Words are strange things; they that can exist in an uncountable number of different forms, fonts, sizes, media; they can be spoken or sung or signed or written or printed or imagined; a handful of letters on a page can make you think, make you unreasonably happy, make you cry, and more; they can be invented anew, they can change their meanings, and they can peacefully die away; they can be chiseled into a gravestone and they can be impossible to get out of your head; they can describe the world and they can change the world. They point at concepts but are also conceptual things in themselves; like fairies in Peter Pan, they only exist because we believe in them.

And if the word is a conceptual art form, then this book – which is full of them (go on, flick forward, it’s true!) – is a sort of gallery of conceptual art.

There’s a tricky question buried in that description of words, which is about the relationship between words and the world. Words don’t resemble the world they seem to describe. The word ‘theatre’ doesn’t look or sound like a theatre. Even onomatopoeic words don’t sound all that much like the things they represent. So how do we come to represent the world through them?

This philosophical question is a practical question for the theatre. What is the relationship between a play on the page and a play in the theatre? Does the text define how the play must be done? If so, in what way and to what extent? If a playwright writes ‘The FATHER nods his head’, some parts of the stage picture are being defined, but others not. We don’t know what the FATHER looks like, his height, how old he is, the colour of his hair, whether he has a beard, what he’s wearing, his expression, and much more. We know that he nods his head, but not how: quickly? slowly? thoughtfully? eagerly? Is it a big vigorous motion or an almost imperceptible gesture? And just because the FATHER nods, does the actor have to? There are many ways of informing an audience that this has happened: someone could read the stage direction out; the gesture could be projected on a screen; it could be inferred from the way the HYPNOTIST reacts; or, if you like, the actor playing the FATHER could nod his head.

Sometimes, the theatre seems to forget that it has these choices to make. In some parts of our theatre, it will seem as if the actor nodding his or her head is the ‘obvious’ or ‘natural’ or ‘correct’ or ‘simplest’ or ‘clearest’ or ‘most real’ way to represent this direction. Since the late nineteenth century, British theatre has been in thrall to the view that the theatre should represent the world by trying to resemble it as closely as possible. This was not always the case; it would be a mistake to think that audiences at the theatre of Dionysus or at Shakespeare’s Globe sat there frustrated that they weren’t looking at more realistic scenery. In those theatres, it would seem, there was a clearer understanding that the theatre functions imaginatively: we are taken into a fictional world and whether that world is represented through realistic sets or random objects or words or sounds that evoke the imagination, these are still conceptual choices we have made.

An artist that Tim Crouch likes to refer to is Marcel Duchamp, one of the first artists to place concepts at the centre of his work, who made an important distinction between retinal art and conceptual art. Retinal art is grasped mainly through the eyes (on the retina); conceptual art is grasped with the mind. In fact, even in the most literal and realistic theatre show, there are always things that only exist for us conceptually; the past and future of the characters, the world offstage, the psychological states of people we are looking at. Most realistic theatre isn’t all that realistic either: actors generally talk much louder than the characters would, walk about in rooms much larger than the characters would; to some extent we just choose to see them as realistic.

Tim Crouch puts the conceptual rather than retinal aspects of theatre front and centre but, in doing so, he reminds us that all theatre is like this. When, in My Arm (2003), he tells the strange story of the play using random objects gathered from the audience, we might well reflect that this is always the case; it’s to some extent arbitrary whether we represent a battle on stage by using onstage actors or offstage sounds or the words of a narrator or a short abstract physical sequence. When in ENGLAND (2007), he has the main character of the play represented simultaneously by two people, we might well reflect that all casting is to some extent arbitrary, that if we can accept young people playing old people or men playing women or poor actors playing Kings or, in the case of James Bond, several different people playing the same person, why should we insist that on stage one character must be played by one actor?

This might make An Oak Tree sound very abstract and airless. But it’s the opposite. What Tim Crouch and his collaborators understand is that the conceptual nature of theatre underpins all theatre from Antigone to Les Misérables, from Waiting for Godot to Run For Your Wife. You can’t have fun or be moved or be filled with joy without partaking in the theatre’s conceptual playfulness.

Several apparently unusual theatrical devices structure the experience of An Oak Tree: first, in a beautifully childlike way, all of the theatre’s transformational power happens in front of us:

HYPNOTIST: Ask me what I’m being, say:

‘what are you being?’

FATHER: What are you being?

HYPNOTIST: I’m being a hypnotist.

This fundamental part of theatre, the transformation of one thing into another thing, one person into another person, is part of what we might call the magic of theatre. But here the magic is spoiled. Or is it? Do we ever really believe in the transformations in front of us? Indeed, the more captivating the transformation that an actor achieves, aren’t we more admiringly aware of the actor? When a movie actor undergoes a massive transformation – make-up, latex reshaping the face, a fat-suit to change the body shape – we always delight in reading the details of the very process that was apparently supposed to erase the actor’s persona.

It might seem as if seeing behind the mask would rob the mask of its effects, but the opposite turns out to be true. Maybe after all we don’t actually ever believe really, like the audience at a bad (or even good) hypnotism act, we pretend to believe in the illusion because we know that, like the fairies in Peter Pan, like words, the theatre only exists if we believe in it.

In An Oak Tree, there is a scene where an actor plays a hypnotist playing a mother, another actor plays a father repeating lines given to him right in front of us, a chair plays a baby and a piano stool plays an oak tree – and, despite all that obvious fakery, it is one of the most moving scenes I’ve seen in a theatre this century.

The second major device is that the second actor is new to every performance. They don’t know the play, don’t know the part, don’t know the lines. They’re told carefully what they have to do, but they literally don’t know where they’re going. It’s an unusual experiment, but it’s also not unprecedented. Parts in a play are called ‘parts’ because, in the Elizabethan period, when it cost a lot of money to have a play copied out, actors would just be given their own lines and cues and find out about the whole play only in rehearsal or performance. (Or, to pick a more contemporary and eccentric example, the actor Tom Baker – best known as the fourth Doctor Who – famously didn’t read the scenes he wasn’t in, claiming that to do so would ‘feel like prying’.) The effect of this in performance, apart from emphasising the way in which the transformation really is happening in front of us, is to intensify the precarious liveness of the performance. With the actor being given bits of paper to read from, instructions over the headset, lines to repeat, instructions to carry out, our consciousness of the possibility of failure is enormously enhanced.

The precariousness of the device fills An Oak Tree with vulnerability and tenderness. The theatre’s provisionality and precarity, its liveness and risk are sharpened and deepened by the second actor, giving new intensity to the dreadful delicacy of the Father’s grief and the Hypnotist’s regret. The actor is the audience’s avatar, knowing little more than we do about the course of the play, and in performance I think you can feel the whole audience willing the second actor on, expressing a kind of care for that second figure, as character and actor and person. It also intensifies our sense of ourselves as an audience, gives us a peculiarly intense sense that we’re all, actors and spectators, in the room together making this all happen. It gives us a fleeting sense of our very connectedness as people, and allows us to glimpse that our mutual responsibilities, our overlapping imaginative landscapes, our care for one another are precious things that don’t just happen, that – like fairies in Peter Pan, like words, like theatre – our humanity only exists if we believe in it.

Caryl Churchill described An Oak Tree as ‘a play about theatre, a magic trick, a laugh and a vivid experience of grief, and it spoils you for a while for other plays’. It does sort of spoil some other theatre for a while, because it acknowledges what other theatre often seeks to ignore. The joy of An Oak Tree is that it explains away how all theatre works, but then does it anyway.

Dan Rebellato

AN OAK TREE

Previewed at the Nationaltheater Mannheim, Germany, 29 April 2005

Premiered at the Traverse Theatre, Edinburgh, 5 August, 2005

Performed by Tim Crouch and a second actor

Co-directed by Karl James and Andy Smith

Original sound design by Peter Gill

Piano played by Simon Crane

Orignally produced by News From Nowhere with Lisa Wolfe

www.timcrouchtheatre.co.uk

THANKS

To all the second actors, past and future.

The Peggy Ramsay Foundation. Mark Ravenhill and Paines Plough. Thomas Kraus and the Nationaltheater Mannheim. The David Knight Hypnotic Experience. The Nightingale Theatre, Brighton. Philip Howard, Orla O’Loughlin and the Traverse Theatre Company. Lisa Goldman and Soho Theatre. Ros Ward and the BBC World Service. James Hogan, Charles Glanville, Andrew Walby and Oberon Books. Martin Platt and David Elliot and the Perry Street Theatre. Dan Fishbach, Michelle Spears, Will Adashak and the Odyssey Theater, LA.

Chris Dorley-Brown. Michael Craig-Martin. Merrit Horton. Annabel Turpin. John Retallack. Alistair Creamer. Tim McInnerny. Simon Crane. Jo Cole. Lisa Wolfe. Julia Crouch. Nel, Owen and Joe. Andy Smith and Karl James for doing brilliantly.

And to the memory of Roger Lloyd-Pack, actor, and Jenny Harris, head of education, National Theatre, 1990–2007.

SECOND ACTORS IN THIS PRODUCTION OF AN OAK TREE

(at time of publication, June 2015)

Rehearsal 2005: Ian Golding, Cath Dyson, Hannah Ringham.

German Previews 2005: Alex Miller, Tom Hartmann.

Uk Previews 2005: Deborah Asante, Emma Kilbey, Dan Ford, Alister O’loughlin, Jo Dagless, Anna Howitt, Matthew Scott, Natalie Childs.

Edinburgh Festival Premiere 2005: Rebecca Thorn, Claire Knight. Sandy Grierson, Ant Hampton, Tom Brooke, Annie Ryan, Sarah Belcher, Al Nedjari, Paul Blair, Hilary O’shaughnessy, Brian Ferguson, Stevie Ritchie, Matthew Zadjac, Gabriela Murray, Ciaran Bermingham, Mark Ravenhill, Waneta Storms, Andrew Clark, Tom Espiner, Jon Spooner, Ross Manson, Jason Thorpe.

Ireland 2005: Barry Mcgovern, Deirdre Roycroft, Dennis Conway, Martin Murphy.

Uk Touring 2006: Amelda Brown, Johnny O’hanlon, Richard Talbot, Nick Walker, Nic Jeune, Pooja Kumar, Richard Croxford, Maria Connolly, Miche Doherty, Kathy Keira Clark, Tristan Sturrock, Mary Woodvine, Emma Rice, Kevin Johnson, Chris Bianchi, Toby Jones, Helen Kane, Hayley Carmichael, Toby Park, James Wilby, Christine Molloy, Christopher Eccleston, Gin Hammond, Roger Lloyd Pack.

Lithuania 2006: Sakalas Uzdavinys.

Latvia 2006: Ivars Puga.

Israel 2006: Marcello Magni, Kathryn Hunter.

Russia 2006: Roman Indyk, Alexander Vartanov, Maria Popova.

Portugal 2006: Beatriz Batarda, Cathy Naden, Andre E Teodosio, Joao Pedro Vaz.

Finland 2006: Taisto Oksanen, Auvo Vihro.

Italy 2006: Lella Costa, Elio De Capitani, Laura Curino.

US Previews 2006: Richard Kamins, Angela Reed, Carmela Marner, Gene Marner, David Bridel, Peter Gaitens, Camilla Enders, Johana Arnold, Ed Vassallo.

Barrow Street Theatre, New York 2006/7: Peter Van Wagner, Rachel Fowler, Lucas Caleb Rooney, Michael Cullen, Mark Blankenship, F. Murray Abraham, Charles Busch, Reed Birney, Randy Harrison, James Urbaniak, Kristin Sieh, Leslie Hendrix, Steve Blanchard, Laurie Anderson, Amy Landecker, John Shuman, Jeremy Bieler, Kelly Calabrese, Michael Countryman, Laila Robbins, Pearl Sun, Joan Allen, Maja Wampuszyc, Christopher Cook, Maura Tierney, Alison Fraser, Frances Mcdormand, Mary Bacon, Tamara Tunie, Ray Dooley, Brooke Smith, John Judd, Richard Kind, Matthew Arkin, Craig Wroe, Michael Cerveris, Marin Ireland, Peter Dinklage, Alysia Reiner, Tim Blake Nelson, Chuck Cooper, Ben Walker, Austin Pendleton, Alix Elias, Mark Consuelos, David Pasquesi, Mike Myers, David Rasche, Chris Eigeman, Lili Taylor, Kathleen Chalfant, Joey Slotnick, Bob Balaban, Adam Rapp, Mary Testa, Hunter Foster, David Hyde Pierce, Stephen Lang, Kathryn Grody, Scott Foley, Jay O. Sanders, Alan Cox, Denis O Hare, Alan Ruck, Lisa Emery, Frank Wood, Mark Saturno, Nicole Orth-Pallavicini, Erik Jensen, David Mogentale, Alexandra Neil, Brian Logan, Katie Finneran, Walter Bobbie, Wendy Vanden Heu

val, Tovah Feldshuh, Carolyn Mccormick, Maryann Plunkett, George Demas, Christopher Durang, Judith Ivey, Jim Dale.

Canada 2007: Patrick Maceachern, Kelly Dawson, Joel Smith, Heather Kolesar, Maiko Bae Yamamoto, Kathryn Shaw, Marcus Youssef, Jonathan Young, John Krich, Erin Ormond, Trevor Hinton

Soho Theatre 2007: Paterson Joseph, Sophie Okonedo, Ruth Sheen, Tracy-Ann Oberman, David Morrissey, Ed Woodall, Phelim Mcdermott, Amanda Lawrence, Anna Francolini, David Harewood, John Ramm, Selina Cadell, Anthony Vendetti, Tracey Childs, Jeremy Killick, Gina Mckee, Juliet Aubrey, Michael Simkins, Saskia Reeves, Celia Meiras, Tricia Kelly, Hugh Bonneville, Paul Hunter, Adrian Scarborough, Linda Bassett, Eve Best, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Gary Winters, Janet Mcteer

UK Tour 2007/2008: Richard Headon, Sam Troughton, Josie Lawrence, Richard Katz, Ben Keaton, Jonathan Keeble, Brigit Forsyth, Claudia Elmhirst, Bill Champion, Louise Dearden, Mark Calvert, Terry O’connor, Deka Walmsley, Jon Whittle, Nathan Rimell, Cora Bissett, Julie Brown, Murray Wason, Siwan Morris, Richard Elis, Ged Stephenson, Vic Llewellyn

Brazil 2007: Rodrigo Nogueira, Guilherme Leme

BBC World Service 2007: Tim Mcinnerny

Singapore 2008: Loong Seng Onn, Jean Ng, Karen Tan, Ivan Heng

Quebec 2008: Kevin Mccoy, Robert Bellefeuille, Anne-Marie Cadieux

Melbourne 2008: Jane Turner, Geoffrey Rush, Julia Zemiro, Kim Gyngell

Hong Kong 2009: Lynn Yau, Jonathan Douglas, Fredric Mao

Brown University, Usa 2009: Matt Clevy

Odyssey Theatre, Los Angeles 2010: Meagan English, Peter Gallagher, Clancy Brown, Lisa Wolpe, John Rubinstein, Kurtwood Smith, Jesse Burch, Dan O’connor, Jennifer Leigh Warren, Beth Grant, Joe Orrach, Peter Van Norden, Stu Levin, Jason Alexander, Peter Macon, Stacie Chaiken, Christopher Michael Moore, Michelle Monaghan, Anne De Salvo, Miguel Sandoval, Lauryn Cantu, Alexandra Billings, Kathleen Early, Carolyn Seymour, Floyd Van Buskirk, Kyle Secor, Alan Cumming, Rich Sommer, Michael Gladis, Megan Gallagher, Alex Kingston, Wendie Malick, Josh Radnor, Alanis Morissette.

An Oak Tree

An Oak Tree